Historians have trouble understanding, for example, why he bravely left Nazi Germany in 1933, effectively denouncing the regime, but then later, living in Austria after its annexation by the Nazis, tried to cozy up to the same evil government. Schrödinger's motives, in many cases, were something like a black box. The exercise brilliantly shows how uncertainty rules subatomic physics. Unlike, say, a marble in a cigar box, whose exact location can be determined precisely, such a quantum particle is described by a smeared-out probability wave.

One of the simplest solutions of his Nobel Prize-winning wave equation is that of a particle in a box.

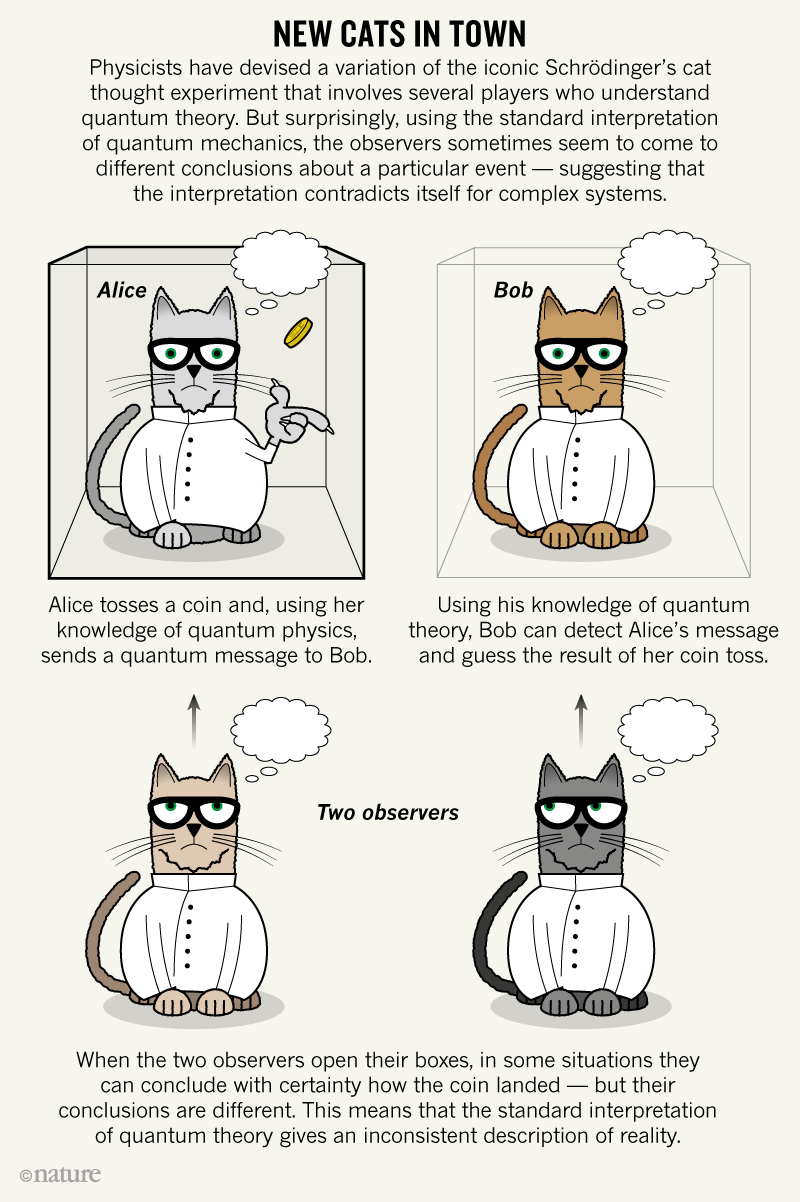

Savvy students of physics know of another box associated with Schrödinger. Similarly, the cat would be in a blended state (as Schrödinger put it, apologetically) of dead and alive. However, according to the orthodox view, the sample would be in a mixed quantum state of decayed and not decayed, until the box is open and an observer takes a measurement. After all, in his famous quantum thought experiment, a closed box is what hides the hypothetical cat from the world, keeping the feline's fate unknown until it is opened.Ĭruelly, within the box a Geiger counter sensitive to the decay of a radioactive sample is rigged to trigger the smashing of a vial of poison - in which case the tabby would be toast. Aside, of course, from the cat, perhaps the image most closely associated with Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger is that of a box.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)